|

|

The Reluctant Pioneer

and Air Mail's Origin

by Nancy Allison Wright

Major Reuben H. Fleet welcomed his new responsibility as officer-in-charge of inaugurating the first U.S. airmail service the way a fledgling pilot welcomes a tail spin at 500 feet. As executive officer for pilot training in the U. S Air Service, Signal Corps Aviation Section, Fleet already had a full plate of duties. He was in charge of establishing America’s pilot training program for all army aviators, an assignment that saw him overseeing 34 fields and as he said, "students crashing every hour of the day." On top of this, Col. H. "Hap" Arnold had given him the added task of training aerial observers. For his story, flash back to May 03, 1918. That was the day the War Department issued an order to the Air Service to begin preparations for launching the airmail service. Oblivious to the pronouncement and the part he would eventually play in executing it, Fleet at the time was traveling between Washington and Dayton, Ohio, hurrying to inspect the crash of a American-produced British de Havilland bomber. This had been the first test flight of the DH bomber powered by the new American-produced 12-cylinder. water-cooled, 400 hp Liberty engine, and it had proved a disaster, ending the life of Col. Henry J. Damm and Maj. Oscar A. Brindley. After inspecting the wreck, Fleet determined the cause of the accident was not engine failure, but a rogue spark plug, wedged between the wing’s trailing edge and the aileron and preventing the plane’s ability to bank on landing.

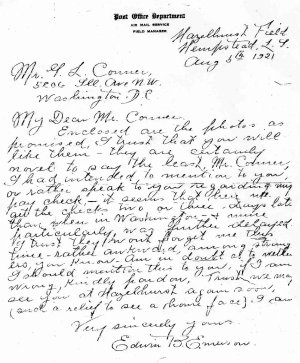

PHOTO: First airmail routes - Washington to Philadelphia to New York. Photo courtesy of the American Air Mail Society.Surprise Assigned to test the second Liberty engine in a DH bomber, Fleet put the plane through its paces. He banked and turned, looped, stalled, kicked it into a spin and landed. But no sooner had he completed the successful trial then he received the order to initiate the world’s first scheduled airmail service. "The order came as a complete surprise ..." Fleet told a gathering of Air Mail Pioneers on their golden anniversary. "...I learned from President Wilson on inauguration day of the mail that the Cabinet had been discussing establishment of an Aerial Mail Service for several months. Bids had been called for but none were received; and, upon recommendation of Col. E. A. Deeds, Air Service Production, that the training would be valuable to Army pilots, had decided to order the Army to fly it." The Post Office Department had formed a joint arrangement with the War Department to inaugurate and operate the new mail service on March 1, 1918, during World War I, and Congress had appropriated $100,000 to launch it. Time Was Fleeting If Fleet was surprised to learn he headed the new operation, he was astonished to discover he had only 15 days to implement the order. That gave him slightly over two weeks to select pilots and find planes capable of flying nonstop between Washington and Philadelphia and between Philadelphia and New York. Fleet asked for a postponement, saying the Army Air Service had no aircraft capable of flying the route nonstop. But Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, stood his ground, saying that even if the war effort had to suffer, the Army Aerial Mail Service would be formed and begin operation on the stated date of May 15, 1918. Why the rush? The press had already been notified. "...the War Department had to do it," recalled Fleet, "even if its aviators had to land in meadows en route and re-tank with gasoline, oil and maybe water."

PHOTO: Philatelic error discovered on May 14, 1918. Photo courtesy of The American Air Mail Society.Fleet ordered six JN-4Hs, single-engine biplanes, powered by 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engines, from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Corporation on Long Island. To accommodate mail bags, he directed the company to leave out the front seat and front control and replace them with a hopper to carry mail. The planes must have double capacity for gasoline and oil, and they must be delivered in eight days. Curtiss agreed to the arrangement, saying they’d suspend delivery of army trainers in order to convert their standard Jennies to the new specs. Fleet contacted his buddy Maj. August Belmont, owner of Belmont Park Race Track on Long Island, for permission to use his park for aerial mail service in New York city. To inaugurate mail from Washington, D.C., the Post Office Department selected the Polo field in Potomac Park and chose Bustleton field near Philadelphia for refueling and transfer. An Arboreal Dilemma Washington’s Potomac Park Polo field was rimmed with trees 30 to 60 feet tall. Within the field stood a covered grandstand and one lone tree. Fleet could do nothing about the grandstand, but he ordered the tree, which had already caused one crash, to be removed by May 14. The Park Department replied that it would take three months to receive permission to cut down the offending tree. Fleet then told the local mechanics to chop down the tree six inches below the ground, cover the hole with cinders, stomp hard on it, then drag the tree outside the park.

PHOTO: Fleet (l) briefs pilot Boyle. Photo courtesy of Jesse Davidson Aviation Archives at JDArchives@aol.com and www.aviationhistoryphotos.com. Noblesse Oblige Fleet selected four of the six pilots to carry the nation’s first airmail -- Lts. Howard Paul Culver, Torrey H. Webb, Walter Miller and Stephen Bonsal. The Post Office, reserving the right to pick the other two, chose Lts. James C. Edgerton, whose father was purchasing agent for the Post Office Department, and George L. Boyle, prospective son-in-law of Judge Charles C. McChord, Interstate Commerce Commissioner. It was McChord who had saved the parcel post for the Post Office Department against pressure to contract it out to private companies. In a display of political savvy, Fleet acceded to the Post Office request that Lt. Boyle be allowed to fly the first aerial mail out of Washington and Edgerton fly it into Washington. Finally, on May 13, 1918, word came that the planes were ready to be picked up and flown to their starting points. Rather than assembled and ready to test fly, however, the planes arrived at New York’s Hazelhurst Field unassembled and packed in crates. With 72 hours until lift-off, Fleet and five of his pilots tackled the staggering job of un-crating, assembling, servicing, checking, warming up, tuning and flight-checking the craft. The men worked through the day and most of the night. By afternoon, only two planes were ready for flight- testing. Fleet ordered Webb, Miller and Bonsal to stay with the planes until they were flight-ready, then told them to fly them from New York to Philadelphia. Too Foggy For Ducks To Fly Fleet and Edgerton in the two completed Jennies and Culver piloting a ordinary Jenny trainer took off in weather too dense to see beyond their wing tips. The fog blanketed Belmont Race Track, their point of departure, like a sheet. Under any other circumstances they would have waited for better conditions, but this was the day before the big inaugural mail experiment and time wasted was time lost. Climbing out of the fog at 11,000 feet, near the Jennie’s ceiling, Fleet flew by magnetic compass and the sun, until he ran out of gas. Luckily, he came out of the clouds at 3,000 feet and glided into a farm yard. From there he bought gas in a five-gallon milk can from the farmer, asked the man which way to Bustleton and took off. He was two miles from his destination when he ran out of gas again. This time he hitched a ride to the airfield with a farmer and sent Culver back with a can of aviation gas to retrieve the plane. Things were not going well for Fleet. The JN-6Hs that Curtiss had rushed to build in time for the deadline had so many things wrong with them, that Fleet and his men labored through another night to prepare them for flight the next morning. "...one gas tank had a hole the size of a lead pencil and we had to cork it up with an ordinary bottle cork, as there was no time or facility to repair it," remembered Fleet.

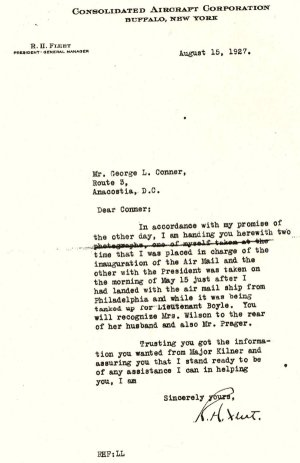

PHOTO: Curtiss JN-4H "Jenny", 1918 At 8:40 on May 18, Fleet took off from Bustleton Field for Washington, D.C. in JN-6H No. 38262, tested and deemed suitable for Lt. Boyle’s triumphant inaugural flight from the capitol to Philadelphia. Landing 25 minutes before the aerial mail show was scheduled to begin, Fleet noted the abundance of dignitaries arriving for the ceremony. President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, showed up, as did Sen. Morris Sheppard of Texas. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt were all assembling. Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson and Second Assistant Postmaster General Otto Praeger wouldn’t have missed the occasion for love or money, and members of the House and Senate Subcommittee on Post Office and Post Roads intended to see how well their allocation had been spent. Because no detailed aerial maps of the route between Washington, Philadelphia and New York existed, Fleet’s pilots relied on state maps to navigate. While Boyle’s fiance handed him an armful of red roses, Fleet strapped the map he’d used to get from Philadelphia to Washington to the upper part of the young man’s leg, hoping that in the course of the flight it wouldn’t blow off. Fleet gave him the correct compass course. Boyle climbed into the cockpit of his Jenny, tightened his leather helmet strap, adjusted his goggles and yelled "contact." Excitement mounted as the ground crew swung the big wooden propeller. The Jenny sputtered, coughed and died. Boyle yelled "contact" again. The engine belched black smoke, then expired. Again he tried. Again and again. "Why in tarnation can't they start that infernal machine?" said Wilson, throwing a withering stare at Otto Praeger, head of the newly created United States Aerial Mail Service. Praeger could only look on helplessly as the mechanics spun the propeller and the powerful 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engine balked. Suddenly, someone shouted, "Check the gas tank." Sure enough, it was bone dry. Fleet had delegated Capt. B.B. Lipsner to make sure aviation fuel was available, but Lipsner had failed in his mission. No doubt Fleet bore the ignominy of the botched order. On his command, the frantic mechanics drained the tanks of three planes parked on the field in order to fill the Jenny. "Contact." The engine roared to life, enveloping bystanders in a cloud of exhaust fumes. Lieutenant Boyle bore down the field, soon becoming airborne, but barely gaining enough altitude to clear the tops of high trees at the end of the runway. Carrying a cargo of 124 pounds of mail, Boyle was on his way to New York with a stop first in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Boyle didn't make it to Philadelphia that day. He got lost, ran out of gas and flipped the Jenny on its back in a plowed field about 25 miles from Washington. When he unbuckled his safety belt he landed on his head. It was once reported that the mail was slipped aboard a train when no one was looking, but in reality Fleet directed Boyle to return the mail to Washington where it was flown out the next day. On the Post Office Department’s recommendation, Fleet gave Boyle a second chance two days later, which he muffed by getting lost again, running out of gas and nearly ending up in the Atlantic Ocean. When the Post Office requested a third chance, Fleet replied, "The request is denied." and ordered him back to flying school. But history had been made. The mail from Washington and New York had gone through. More importantly, other pilots on the relay team completed their flights, and the newspapers were generous with their praise. Air mail was on its way. Fleet and his earliest supporters could not have dreamed of the contribution that day would make to the development of aviation. But the distance to travel from Jennies to jets would be long and fraught with perils and uncertainties. For his effort Fleet was presented with a Hamilton wrist watch engraved to commemorate the inaugural flight. As promised he returned to his other duties with the Army Air Service, now separated from the Army Signal Corps. Fleet went on to distinguish himself in the field of aviation. In 1923 at Buffalo, N.Y. he launched the Consolidated Aircraft Co., which became the Convair Corp., building more than 11,000 of the World War II bombers and PBY Catalina planes. Fleet retired in 1949 from the firm which had merged as the Convair Division of General Dynamics Corp. He died at the age of 88.

Nancy Allison Wright is editor of the Air Mail Pioneers News, a periodic newsletter of Air Mail Pioneers. Her father, Ernest M. "Allie" Allison, was former national treasurer and western division president of Air Mail.Pioneers. |

History |

Air Mail Pilots

|

Photo

Gallery |

Flight Info

|

Antique Airplanes

|

Members |

|

copyright © 1999 Nancy Allison Wright, President Air Mail Pioneers

|